‘TELLTALE FORMS’

Studio shot of work in progress for a new one-man show at Pangolin London entitled Telltale Forms, running from 8th May until 16th August, 2025. This exhibition at its simplest aims to include work from over four decades, reflecting my search for a pertinent personal and cultural narrative relevant to the time in which we live. In my early work I used nature as a metaphor to describe the human condition but increasingly I have focused on our relationship to nature itself and our place within it.

Jon Buck

April 2025

‘PATTERNS OF CHANGE’

‘Patterns of Change’ is a recent body of work commissioned for a major exhibition on the mezzanine level at Kings Place, London, running from 6th September 2022 until 4th March 2023.

This area of the building is a busy public thoroughfare and this very much dictated the nature of the work which had to be wall-based. In order to use the space available in a dynamic and innovative way, it also needed to be of an appropriate scale to the architecture of the building. To fulfil this brief, I created three large birchwood reliefs to be sited in the larger spaces and a series of new woodblock prints and drawings to be hung together in groups or blocks.

The large wooden reliefs were something of a new departure both in scale and materials. However, as a result they became a successful link between my previous two-dimensional work and the more fully formed three-dimensional sculptures. In fact, I had employed a similar process previously on a much smaller scale to make woodblock prints and the series of prints in this exhibition are made with exactly the same technique. The large triptych reliefs can be seen to refer to this process and in theory could themselves be used to make very large prints. They also make a visual link to the small sculptures exhibited, whose raised and patterned surfaces echo the patterns on the reliefs as well as the prints and drawings.

Furthermore, the subject matter of the whole of this exhibition is inspired by the evolutionary process of the living world and could be seen to have an analogous link to the creative process of making art.

Jon Buck

November 2022

‘MARCH OF MUTABILITY’

In more recent years it has been come more apparent that the process of evolutionary change is not one solely of competition and conflict. In consequence, the drawings that accompany and complement my sculptures not only reflect and expand on the ideas discussed above but also refer to evolutionary processes that are more benign in nature. Historically, Darwin’s metaphor for the evolution of life was that of a tree with an ever-expanding canopy of branches emanating from a single trunk, literally the ‘Tree of Life’. In the light of more contemporary research it has become apparent that this is not a completely satisfactory analogy. It is now known that many of the branches are not only divided and bifurcated but, quite unlike a tree in reality, there are many places where the branches have fused back together forming a lattice-work. This model can more accurately be described as a ‘Web of Life’.

As long ago as 1969, biologist Lynn Margulis conjectured that some of the most significant moments in evolution were the coming together of completely non-related organisms in symbiotic relationships. As a result, all complex life, including ourselves, is a story of what she called an ‘intimacy of strangers’ or as others have put it, we are all ‘lichens’ living in symbiotic relationships with other organisms either on us or within us. Surely in this light alone it is incumbent upon us to urgently search for a new secular sanctity for the whole network of life.

Jon Buck

July 2021

‘MARCH OF MUTABILITY’

In the nineteenth century however, Darwin and Wallace rocked the foundations of belief in a supernatural creator with their theories of evolution. Since then science has brought to light many of the evolutionary mechanisms that govern how the Earth came to be inhabited by such a prolific and diverse web of life. What a huge irony then, that just as we are coming to understand the underlying principles of how life began and developed, it is we humans who threaten this very diversity. We are now living in the era we call the Anthropocene.

It could be said that mathematics is science’s own discrete language but luckily for the majority of us, to effectively communicate its theories and discoveries it often employs more allegorical symbols . In 1973 the biologist Leigh Van Valen proposed just such a metaphor to brilliantly describe a universal rule for evolutionary change. He advanced the theory that all organisms are caught in an everlasting arms race. To survive they must continually evolve and change in order to compete against other ever-mutating opposing organisms. He famously entitled this thesis The Red Queen Hypothesis, referring to Lewis Carroll’s character in ‘Alice Through the Looking Glass’. The Queen, as part of a bizarre and counter-intuitive chess game, informs Alice that according to the rules:

‘…it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.’

At the end of the 1990’s, another biologist, Anthony Barnosky, introduced a new player to this evolutionary chess game and also coined the phrase that is the title of this exhibition. He maintained that while the Red Queen Hypothesis adequately explains the ongoing pressure of gradual biological evolution, one should also take into account that there are occasional huge catastrophic events that interrupt gradual change, causing mass extinctions and subsequent rapid transformations. He referred to this idea as The Court Jester Hypothesis and although it is not exactly clear why, my thoughts are that a jester is normally a maverick or wild card and he is completely unpredictable because he does not play by the rules of the main game.

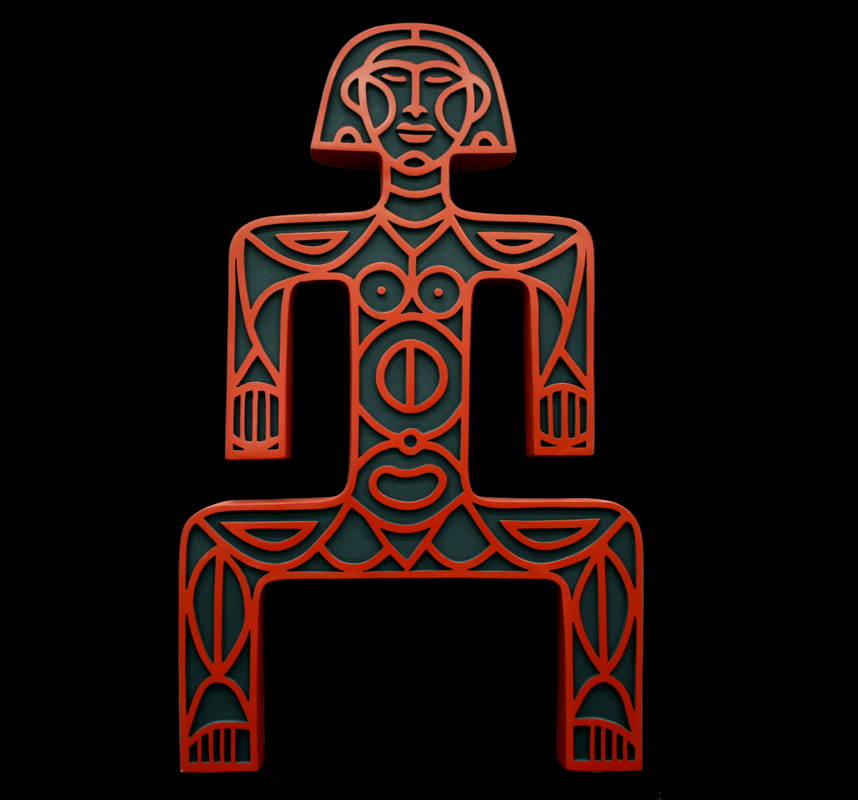

These intriguing ideas have stimulated me to make a new series of works, in what I like to think is a parallel process of artistic evolution. On the surface of my sculptures I have created patterns that have spontaneously developed. Each individual glyph or element in the pattern has had to respond to and change according to the shape of its neighbour. This echoes and refers to the biological processes that form the living networks of natural organisms in the real world. The result is that these individual elements are now less representational than on some of my previous sculptures and perhaps it is not too fanciful to imagine them to be in the very act of modification or evolution.

The sculptures underlying these new patterns are intended as timeless representations of The Red Queen and The Court Jester and in the newest pieces the jester has further evolved to become what I have named The Fool. The difference between the two in my mind is that the Jester’s’ role is to behave outrageously, whereas The Fool is out of control and refuses to acknowledge his harmful actions. In these newest sculptures, I am proposing that it is we humans who are The Fool and much like Barnosky’s Jester it is we who are having an unpredictable and devastating effect upon the essential patterns of biodiversity and the whole web of life.

Jon Buck

July 2021

‘TIME OF OUR LIVES’

‘Taking the Toll’

The sculpture on the above left is one of three different bronze bells made for my forthcoming exhibition at the beginning of May, entitled Time of Our Lives. On the right is its two metre high digitally enlarged counterpart being worked on before casting.

I have chosen to use the bell motif for a number of reasons. There is of course a long-standing tradition of making bells in bronze casting but in addition bells are redolent with cultural meaning and there is an inherent ambiguity in how they are used. In many societies bells are rung joyously in celebration but at the same time they can also be tolled as dire warnings of imminent danger.

I would like my current work to embrace both these aspects. The surfaces of the bronzes have an intricate network of relief motifs celebrating the biodiversity of the natural world. At the same time these bells can also be seen as a visual lament for the pressures we are imposing on our natural environments and the creatures that inhabit them. The title of the show ‘Time of Our Lives’ underlies these sentiments. While in the last forty or fifty years many of us humans have ‘never had it so good’, in that same period according to the WWF, the earth has lost more than half of its wild animals.

RED QUEEN RULES

These two newly completed editions of my sculpture Red Queen Rules confront each other as if vying for our attention, which interestingly hints at the subject that inspired them.

The title comes from the term Red Queen Hypothesis, a phrase science has borrowed from Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass, to suggest that in the natural world organisms must continually evolve if they are to successfully survive and reproduce.

However, ever since Darwin’s explanation of sexual selection it has remained puzzling how many creatures in the natural world make themselves so conspicuous, because on the face of it, this seems counterintuitive for survival. Since Darwin, intervening theories have conjectured that these sexual ornamentations are indeed a ‘handicap’ and must have evolved to prove to a prospective mate the overriding fitness of the suitor.

New research counters this approach, suggesting that mate preference is more arbitrary and is simply an aesthetic choice usually made by females, comparing the male’s appearance or performance to a corresponding template within her neurological network. This can be a song, a display or a visual pattern. If a slightly altered version of these traits is preferred then that influence the mate that is chosen. This to say that in sexual selection, many creatures have like us what Darwin called “A taste for the beautiful” and as such suggests that culture and nature coevolve to make new creations. Which in a way, sounds like art?

NEW WORK: TOCSIN

This is an image of a digital scan of a sculpture entitled ‘Tocsin’. It is part of a new body of work that essentially celebrates the forms of nature’s biodiversity. However at the same time these new works directly address the vulnerability and the threat that humans place upon the rest of the biological world.

This work takes the form of a primitive bell whose surface is embellished by a raised pattern of animal glyphs. These symbols represent a small sample of the incredible diversity of the evolution of life. On each side at the centre of the pattern lie two vultures facing each other. These birds are an essential part of the great cycle of life but for some they are iconic symbols of death. It is somewhat ironic then that these great birds are themselves under a very real threat of extinction from human wilful disregard for the way we pollute the world.

The title Tocsin seems appropriate: although it has occasionally been spelled like its homonym toxin, tocsin has nothing to do with poison. Rather, it is derived from the Middle French word toquassen and ultimately from the Latin verb toccare (“to ring a bell”) and the Latin signum (“mark, sign”), which have given us, respectively, the English words touch and signal. Tocsin long referred to the ringing of church bells to signal events of importance to local villagers, including dangerous events such as attacks. Its use was eventually broadened to cover anything that signals danger or trouble.

ARK: HIGH AND DRY

In this image I am working on the final surface of one side-panel of the polystyrene enlargement of the sculpture Ark: High and Dry (in the photo it is resting on its top edge and is therefore upside down in relation to its intended orientation: see inset). The whole sculpture has been enlarged digitally by Pangolin Editions’ digital team and will be cast into bronze using sand-moulding techniques. The final full-scale sculpture will be five times larger than my original maquette, standing at over two metres high and more than three and a half metres wide. It is proposed that it will be shown for the first time in an exhibition in Chester this summer.

IN THE STUDIO: JULY 2016

SOMETHING OF THE MARVELOUS *

“It is a wholesome and necessary thing for us to turn again to the earth and in the contemplation of her beauties to know the sense of wonder and humility.”

– Rachel Carson, The Sense of Wonder

In recent my work there has been a shift away from what I refer to as ‘animals of the mind’, a relatively small lexicon of animal familiars used as imaginative metaphors of ourselves. Gradually I have begun to expand the variety of animal symbols with the specific intention of investigating the relationship we have to the natural world.

I see this change as a shift of focus away from the introspective inner world to a wider perspective, which looks at the incredible variation of ‘life’ and the context in which we exist alongside it. We cannot ignore the fact that as we as a species increase at an alarming rate exponentially, the diversity of life around us decreases. The intention of this new work is not to be an overtly pessimistic critique but by celebrating the forms that make up the great tapestry that is the web of life, it inevitably reminds us of its fragility and vulnerability to our pressures: humanity versus biodiversity.

Contemporary science confirms what we feel intuitively, that biodiversity is the key to the survival of a healthy planet. In Elizabeth Kolbert’s book Sixth extinction: An Unnatural History, she stresses that we are part of the whole (life on Earth) but nonetheless we are its main problem. She uses the image of an ark as a metaphor for today’s conservation work and in her research she discovers that a contemporary ark takes the form of a frozen bank of genetic material, what she calls a frozen zoo. It is a sobering thought that the future of many of today’s species may be reliant on some form of cryogenics.

The biblical myth of Noah’s flood as we know, tells that man, as nature’s guardian, is given the responsibility of rescuing and ensuring the survival of all the creatures that inhabit the earth. It is indeed ironic then, that a new ‘ark’ is required once again due to the threat that we ourselves pose to the diversity of the natural world. This is not a futuristic dystopian fantasy: Kolbert tells us that one third of all coral reefs, a third of sharks and rays, a quarter of all mammals, a fifth of all reptiles and a sixth of all birds are already in imminent danger of extinction.

The threat of impoverishment to our planet not only poses a threat to our own physical health; the loss of so much aesthetic beauty also has an enormous effect on our psychological wellbeing. Within most of us there is a residual recognition of a common inheritance, for many it engenders a need to embrace the beauty around us and to acknowledge it is something that we lose at our peril. As the writer Ian McEwan observes:

‘Contemplating the beauty of the physical world is a source of great joy.’

Conscious that sculpture, at least to my mind, is not the best form of narrative art, I nevertheless believe that a narrative content is an important aspect of the relationship between artist and audience. Content in art is a reflection of how we perceive ourselves in time and place; it expresses how we feel about what we know.

The novelist Colm Tóibín remarked in a recent interview that ‘ideas’ are the death-knoll of creativity. He suggested that one cannot directly express philosophy in art. All one can do, is take small elements of life and describe them in the best way one is capable. Building these together, one begins to form some sort of truth, some sort of reflected reality that triggers recognition and perhaps understanding.

I think there is some truth in what Tóibín says and I would like to think that my recent work carries some of this process in its creation. To a large degree I have concentrated on the aesthetic patterns developed by my making process. This, combined with my own observations from the real world of natural history, have the affect of being a reflected form of biodiversity. These are not the literal descriptive images as captured by the lens of the camera but are distilled, concentrated forms that might be seen as the essences that combine to form a web of life. The anthropologist Ellen Dissanayake calls this process of transforming reality into art ‘making special’. She says:

‘I suggest that what artists do in all media can be summarized as deliberately performing the operations that occur instinctively during a ritualised behaviour: they simplify or formalize, repeat (sometimes with variation), exaggerate, and elaborate in both space and time for the purpose of attracting attention and provoking and manipulating emotional response’

* In all things of nature there is something of the marvellous.

Aristotle

Argentum Vivum

This new work ‘Argentum Vivum’ has been cast in sterling silver. The title comes from the Latin, which literally means, “living silver”. The English translation for this term is Quicksilver, which itself is derived from the Old English word cwicseolfor, quick in this case meaning in the sense of being alive. Quicksilver is often used as a more poetic way to talk about the element mercury because of its colour and liquid properties. Some of the forms on this sculpture are rather mercury-like in appearance, however I have used the title to describe this sculpture more literally. Made in silver not mercury, the inference is that life in the form of symbolic glyphs is contained within a flask of liquid. This man-made containment perhaps suggesting not only our fascination with the study of the origins of life but ultimately our responsibility to make sure that we preserve its diversity.

A new exhibition will start at Pangolin London, King’s Place at the beginning of May 2015 exploring the use of colour in my work. The two examples above are new images that will be part of this show.

Polly Bielecka, the gallery director, discusses this subject in her introduction to the catalogue:

“Jon Buck has always regarded colour as one of the sensory delights of the human experience. Whilst colour is not traditionally associated with sculpture, Buck has spent much of his career experimenting and exploring its impact and ability to enhance sculpture.

When Buck first began exhibiting in London in the early eighties, his highly coloured resin and glass fibre works led him to be shown together with a group of disparate artists whose highly realistic work coined the term ‘superhumanism’. Whilst successful, he soon realised that his materials were inadequate for outdoor works and so began his long and fruitful collaboration with the bronze foundry, Pangolin Editions.

At this time, the palette available to artists in terms of patina was a dull and subdued range of browns and greens and in order to keep the work dynamic Buck had to alter his approach by developing the surfaces of his forms either with small repeated motifs or unusual textures. Working with Rungwe Kingdon at Pangolin Editions, Buck began to experiment with patinas. Together they discovered new vibrant reds, electric blues and soft flesh-coloured pinks as well as investigating the possibilities of incorporating raw pigments to the surfaces and painted lines drawn directly into the form itself. Through this close collaboration Buck gained the confidence to break free from the traditional constraints of bronze casting and has over recent years produced a unique and vibrant body of painted bronzes.”

Polly Bielecka

Gallery Director

Pangolin London

February 2014:

These are two of the finished originals that I have been working on in recent months. They make up part of an exciting new body of work that will be shown in my forthcoming solo exhibition, “WITHOUT WORDS”, at Gallery Pangolin this summer, see News section for full details.

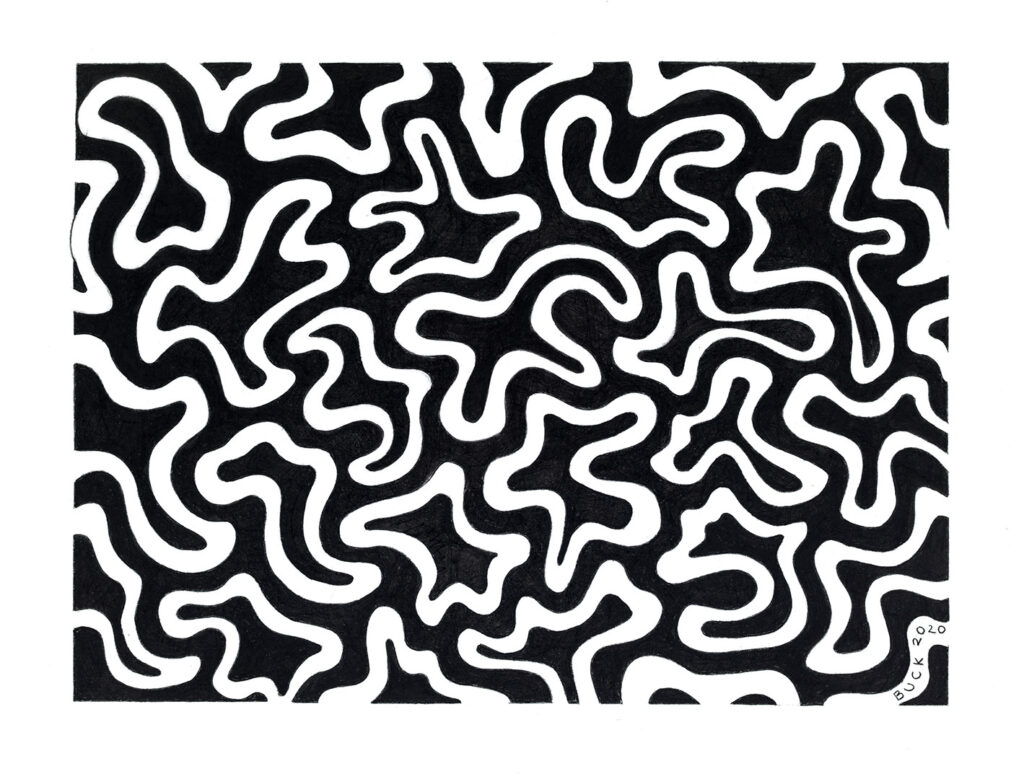

Recent work includes a series of woodblock prints made for Gallery Pangolin’s exhibition, Sculptor’s Prints and Drawings.

Making relief prints is often essentially a carving process. Material is gouged from a flat plane to leave a positive form that can then be covered in ink to transfer the image onto paper. As a sculptor however, I am used to the reverse process and my modus operandi is to work from the centre out. In several of my sculptures, Part of the Puzzle, Repository and Red Queen Rules, for example, made for Turning Inside Out at Pangolin London 2012, I have taken this process one step further. I have reversed what I would normally make as drawn negative lines on the surface and made them positive raised forms. The resulting sculptures take the appearance of printing blocks in the round and in fact they could possibly be used as such.

To make the woodblocks for printing I decided to use this positive building-up process rather than the conventional gouging-away method. The result is a rather stencilled effect, which I like as it reflects the reproductive nature of the printing process and connects the prints strongly to my most recent sculptures.

I also expanded this idea of printing block and artwork being one and the same thing in a couple of prints made on wood, which I have called Pyroglyphs. The images were made by firstly making ‘drawings’ in welded metal rods and then heating and branding them onto sheets of birch-laminated plywood. These images were developed from abstractions of human, bird and dog motifs and directly relate to a series of drawings called Behind the Eye made for Turning Inside Out. Perhaps not surprisingly they seem to echo and reflect many of the ambiguous geometric symbols found in art since time immemorial.

My current studio work continues to develop this theme of making objects that to some extent blur the separation between what can be described as a drawing, a sculpture, a print or at least the printing block.